MHT Day 14: Back to the 1805 Missouri Route

A leisurely beginning today in Billings had me on the road about 9 a.m. and for three hours I had a pleasant ride northward through gigantic fields of hay, mixed prairie grasslands, some hill country and finally next to some small mountains, all under a beautiful blue sky. Then it got hot, and the rest of the afternoon was in the 90s and the thermometer stood at 98 degrees when I parked the bike for the day in Havre, Montana.

As I rode down the black asphalt strip with my booted feet up and the cruise control on, every once in a while I spotted a lone pronghorn or a small group of them grazing near the road. The pronghorn are in North Dakota as well, but I didn’t see any during my passage through there. The men of the Expedition had never seen pronghorns and referred to them throughout their journey as goats. Lewis the naturalist made sure he preserved skins, horns and bones to take back to the scientists in the states to examine.

The mountains in the background are the “Little Rocky Mountains” and were a place of spiritual significance for Natives for hundreds of years before Lewis and Clark paddled past them.

When the Expedition first travelled west across what is now Missouri, trees were in abundance, but the further west they went the fewer trees they would see. By the time they reached North Dakota and, especially, Montana, the only trees to be seen would be those along the Missouri River. When they climbed the river banks and stood atop any of the nearby hills for a long-range look at the vast, unexplored county, their camps on the banks of the Missouri under cottonwoods and willows must have seemed like an oasis in a desert, and in some ways it was.

When I reached the Missouri today on my way north, I crossed it at a point two miles downriver from where the Corps of Discovery camped May 24, 1805, about six weeks after they left the Mandan villages. That day Lewis described the country they were going through:

The country high and broken, a considerable portion of black rock and brown sandy rock appear in the faces of the hills; the tops of the hills covered with scattering pine spruce and dwarf cedar; the soil poor and sterile, sandy near the tops of the hills, the whole producing but little grass; the narrow bottoms of the Missouri producing little else but Hysop or southern wood and the pulpy leafed thorn . . . . game is becoming more scarce, particularly beaver, of which we have seen but few for several days the beaver appears to keep pace with the timber as it declines in quantity they also become more scarce.

This section of the Missouri is far enough away from the first of the six lower dams that it retains the character of the river that Lewis and Clark saw. I’ve had few opportunities to see it as they saw it, and I stood on shore for several minutes imagining paddling the dugouts or pulling with ropes the larger boats. The water was no doubt clearer 200 years ago before farming, ranching and upriver effluent changed its color.

Upriver, about 30 miles from where I crossed today, is an area known as the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, where the river is accessible only by watercraft. It is the least changed part of the Missouri River since 1805. I had planned to canoe that section of the river for three days with river guides and an historian well-versed in the Lewis and Clark adventure, camping along the way on the same sites Lewis and Clark camped. But when I began to trim this trip down, that outing was cut from the itinerary. Maybe someday I’ll come back and do the canoe trip.

I had one other planned stop today that is only indirectly related to the Lewis and Clark Expedition: The Bear Paw Battlefield, part of the Nez Perce National Historic Park. I have to jump ahead chronologically a little for this part of the blog to make sense.

In the fall of 1805, the Nez Perce in present day Idaho rescued a starving Corps of Discovery after a harrowing, 11-day journey across the Bitterroot Mountains. The Nez Perce also treated them well on the 1806 return trip. So how did our government reward their treatment of the Corps? After the U.S. gained control of the Oregon Territory in 1848, the government began clearing the way for white settlement and gold miners by “negotiating” treaties with the Nez Perce and other tribes that took more and more of their traditional hunting grounds until they were left with only 5% of their original ancestral land. Many Nez Perce, especially younger warriors, refused to go along with this land grab and war broke out in 1877.

On this site in northern Montana the fleeing Nez Perce surrendered and the Nez Perce War of 1877 ended.

Many Nez Perce decided to flee the reservation and seek refuge in Canada. For 126 days covering more than 1100 miles, the American Army chased and sometimes fought with the escaping band. 40 miles south of the Canadian Border, 400 Army troops finally caught up with the 100 Nez Perce men and 600 women and children. They attacked and besieged the camp for seven days before Chief Joseph finally surrendered to General Miles on October 6, 1877, with these words:

I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Tulhuulhulsuit is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say, “Yes” or “No”. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are, perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.

This monument showing Chief Joseph surrendering to Colonel. Nelson Miles stands in mute testimony to a sad part of American history.

The Indians were marched to Oklahoma where many of them died in the following months.

Because of the kindness shown by the Nez Perce to Lewis and Clark, I wanted to pay my respects by standing where Chief Joseph stood. When I went to the NPS-administered Bear Paw Battlefield today, I was the only person there. No tourists. No park rangers. Just me and the silent wind blowing through the tall prairie grass. I was moved by the stillness of the place where so many died and humbled by what was before me.

My final stop of the day was in Havre, Montana, where nothing related to Lewis and Clark occurred but where my oldest granddaughter, who I had not seen in about 4 years, now lives with her husband and my great-grandson Leo. Leo is in Wisconsin with my daughter enjoying his summer of being spoiled, but I had a nice dinner with Meghan and Wakefield and enjoyed catching up.

My final stop of the day was in Havre, Montana, where nothing related to Lewis and Clark occurred but where my oldest granddaughter, who I had not seen in about 4 years, now lives with her husband and my great-grandson Leo. Leo is in Wisconsin with my daughter enjoying his summer of being spoiled, but I had a nice dinner with Meghan and Wakefield and enjoyed catching up.

For those readers who have expressed concern about the paucity of pie on this trip, please note that this is in front of me in the above picture:

MHT Day 13: What’re the Odds?

Montana is big. Very big. 147,000 square miles. Big Sky County and all that.

So what are the odds that two people from Haywood County, North Carolina, could bump into each other there? Pretty huge, right? But it happened.

As I walked out of the interpretive center at Pompey’s Pillar (more about that in a minute) I saw a familiar person heading to take a closer look at the rock. It was Jim Pierce and his wife Linda. Jim is one of my co-workers at Habitat for Humanity. I knew he and Linda were headed for Alaska pulling a camper, and he knew I was headed for Oregon following the Lewis and Clark Trail, though no plans had been made to cross paths. But we did.

Once we got over the shock of seeing each other in the middle of Montana , Jim and I climbed the 200 foot high rock (there were stairs) while Linda waited below out of the hot sun in the air conditioned visitor center.

Jim Pierce and I laugh as Linda documented our chance meeting with my camera so we could prove it really happened.

Jim and I strike our best Lewis and Clark poses in the replica canoes similar to what Clark would have used paddling down the Yellowstone river in 1806.

So, how did it happen that we met today? I decided several months ago that I would take a detour today from following the 1804 route up the Missouri River and instead see part of the route taken by Clark on the 1806 return trip from the Pacific Coast after he and Lewis temporarily parted ways once they re-crossed the Rocky Mountains. Lewis went north to try to locate the northernmost reaches of the Louisiana Territory, while Clark took several of the men and Sacagawea and her infant to look for and map the Yellowstone River. Their plan was to meet again at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers in early August.

I wanted to cover as much of their travels as possible, and the Missouri River is largely a series of Lakes in northern Montana, so today I backtracked Clark’s route down the Yellowstone River, looking particularly for Pompey’s Pillar. But I also decided yesterday that since I was so close to the site of the historic 1876 Battle at the Little Bighorn (which has nothing to do with Lewis and Clark) that I would add 100 miles and three hours to today’s ride for a brief visit to that well-known battlefield.

It was hot when I got to the National Park Service’s popular site on the Little Bighorn, so I watched a brief film in the crowded and stuffy visitor center, walked to the famous location where Custer and 41 of his men died on a small hill, then motored along a road that traces the course of that battle. Every American over the age of 10 has probably heard of Custer’s Last Stand, but to visit the site and imagine the chaos that unfolded that day is to understand why we preserve such relics of the past. An hour wasn’t enough time to truly appreciated those days in late June 1876, and I’d like to return when I have more time to study and understand all that happened.

The hill at the Battle of the Little Bighorn where Custer and his men fell. The stones mark the location where the men fell, not where they are buried. Throughout the site, there are similar stones where several hundred other soldiers died fighting the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho who simply wanted to be left alone and free to roam and hunt on their ancestral lands.

After I left the battlefield, I headed back to the Yellowstone River, narrowly avoiding a GPS-chosen road that was gravel for 14 miles, and found the location of the Department of the Interior administered Pompey’s Pillar National Monument. Which, of course, is where I had that Strange Encounter of the Habitat Kind that still boggles my easily boggled mind.

Pompey’s Pillar or Tower pretty much as Clark saw it in 1806.

Where was I? Oh, yes. Pompey’s Pillar. On a rainy, windy July 25, 1806, Clark recorded in his journal that “at 4 P M arived at a remarkable rock Situated in an extensive bottom on the Stard. Side of the river & 250 paces from it. this rock I ascended and from it’s top had a most extensive view in every direction. This rock which I shall Call Pompy’s Tower is 200 feet high and 400 paces in secumphrance and only axcessable on one Side which is from the N. E the other parts of it being a perpendicular Clift of lightish Coloured gritty rock on the top there is a tolerable Soil of about 5 or 6 feet thick Covered with Short grass. The Indians have made 2 piles of Stone on the top of this Tower. The nativs have ingraved on the face of this rock the figures of animals &c. near which I marked my name and the day of the month & year.”

And his carving on the rock is still visible, protected now by bullet-proof glass to prevent imbecilic vandals from defacing it. Over the years hundreds of people have also carved their names in the rock, but it’s now protected by a camera and a staff person.

“W Clark July 25 1806

This signature on an odd rock named for the infant son of Sacagawea in the middle of Montana is the ONLY physical evidence to be seen along the trail to prove that Lewis and Clark were there. Her son, by the way, was named Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, but Clark called him “Pomp” or “Pompey.”

Other than the field of soybeans in the foreground, this is pretty much the view of the land that Clark had looking west from the top of Pompey’s Pillar. The earlier rains of July 25, 1806, must have cleared because Clark saw snow-covered Rocky Mountains to the southwest. “after Satisfying my Self Sufficiently in this delightfull prospect of the extensive Country around, and the emence herds of Buffalow, Elk and wolves in which it abounded, I decended and proceeded on a fiew miles

Tomorrow I’ll return north to continue to retrace the 1804 route, recrossing the Missouri and detouring once again, this time for a brief visit with a granddaughter.

Oh yes we did.

MHT Day 12: Overwinter at Fort Mandan

I should start this post by noting that the day turned out much better than I expected when I fired up the V-Twin this morning. For months I had looked forward to a stop at the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center and a re-creation of Fort Mandan in Washburn, N.D. When I looked at the state parks’ website for this facility this morning, it didn’t list operating hours. So I called the phone number listed for the park and, as expected at 7:30 a.m., got a recorded message, which gave the operating hours as 9-5 Monday through Saturday. Closed Sunday. To say I wasn’t happy would be a gross understatement, but there wasn’t anything I could do either, so I scratched that visit and headed for the Knife River Villages National Park site 25 miles west Washburn that was open today. The route from Bismark took me past the Washburn Interpretive Center/Fort Mandan, so I pulled in the parking lot thinking I might get a picture of something on the outside. To my great surprise and delight the center was open and is always open on Sundays. The staff inside promised to work on fixing the website and phone recording.

The staff at the Interpretive Center also told me that a tour of the fort two miles down the road was about to start and I should go there first. So back on the bike I climbed and roared off to the fort.

The Corps of Discovery landed near a large Mandan village in late October 1804 and there they would stay until spring. The original plan had been to send the keelboat back to St. Louis before winter set in, but delays along the way convinced the captains to wait until the spring to split the party, with seven men returning to St. Louis and 30 continuing westward. That meant building a fort with accommodations for all of them for the winter. When completed, the fort was a triangular shape with two rows of huts with upper lofts forming two legs of a triangle and a log picket front with a gate forming the third.

Sergeant John Ordway also kept a journal and from his writings we can watch the progress of the fort building. (Spelling is as in the original.) November 2, 1804: laid the foundation of one line of our huts, which consisted of 4 Rooms 14 feet Square. the other line will be the Same. November 13, 1804: we unlaoded the boat for fear the Ice would take it off we put the loading in the Store house, all though it was not finished, but we continued the work November 17, 1804: the party all moved in to the huts November 27, 1804: we finished dobbing & covering & compleating the remainder of our huts December 1, 1804: we commenced bringing the pickets & preparing to picket in our Garrison December 24, 1804: we finished Setting pickets & arected a blacksmiths Shop.

Nearly six weeks passed between the time the building started and the day the final pickets went up. But in fairness to the members building this fort it should be pointed out that during this time two cold snaps lasting several days each dropped temperatures to minus 30 to minus 44 degrees. Work on the fort in those conditions would have resulted in several cases of frostbite or frozen fingers.

Melissa was the tour guide today and nine years on the job have given her tremendous knowledge about the fort and an appreciation for what it took to build and live in it. She is standing in the middle of the triangular parade grounds. Four “huts” would have been on each side and two additional storage rooms completed the rear of the structure.

The re-created fort represents the best efforts at historical accuracy, but since no one knows exactly what the fort looked like, historians have had to rely on a sketch and a couple of recorded measurements. One of the things I enjoyed about this re-creation is that the rooms are furnished with tools, weapons, personal goods, clothing, furs and other items that are meant to be handled by visitors. They’re all replica items, but it’s much more effective to hold a blunderbuss than to simply see it behind plexiglass.

The tour normally lasts for 30 minutes but Melissa was extremely forbearing and allowed me nearly an hour and a half during time which I peppered her with questions for which she always had a good answer. Today, I was fortunate once again in finding an historic site staff member willing to go the extra mile.

Melissa and I stand in front of the fort, showing the pickets, the gate and one row of huts. For years the site was funded and operated by a 501-C-3 organization. Four years ago the state of North Dakota stepped up and added the site to their state park system.

Following the extended tour, I returned to the interpretive center for a much different tour. The center has exhibits on several topics, including the 1804-1806 expedition and a room dedicated to Sakakawea/Sacagawea/Sacajawea. The spelling, pronunciation and meaning of her name are still hotly debated; even her tribe of origin is not agreed upon. Most, but not all, scholars believe she was a Shoshone captured by the Hidatsa, with whom she was living with her French-Canadian husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, when she and he were added to the expedition in the winter of 1805 at Fort Mandan. The Interpretive Center was well done and often repeated and confirmed what I had read about the expedition preparing for this adventure.

What was new to me was the display on the impact of smallpox on the upper Missouri tribes from the 1770s through the 1830s. Several different epidemics swept through the area periodically, often killing 40% to 50% of a tribe. But the final and worst epidemic occurred 30 years after Lewis and Clark completed their voyage. In 1837, a catastrophic epidemic killed off 90% of the remaining Mandan, who had never been vaccinated, and 50% of the remaining Hidatsa. Those two tribes combined with a decimated Arikara tribe to form what is known today as the “Three Affiliated Tribes,” whose people largely live on a reservation in Central North Dakota.

I tried on a buffalo robe in the Interpretive Center. It would have been warm, but quite heavy to walk around in during sub-zero weather on the Missouri River.

After finishing up at the Interpretive Center, I headed down the road to the Knife River Villages site run by the National Park Service. This site preserve traces of three Hidatsa villages that would have been known to and visited by Lewis and Clark. It was here that Sacagawea and Charbonneau left the group on the return trip in 1806. All that remains above ground are circular depressions where earth lodges would have been erected. Artifacts below ground, however, are still being discovered by archaeological digs such as the one I observed today. The site also has a re=creation of a 50 foot diameter lodge that would have typically held 10-20 people, food stores, dogs and sometimes horses.

Circular depressions are evident on a walk across the prairie near the Missouri River. The three villages would have held between 30 and 70 earth lodges with a total population of about 2,000 Hidatsa.

Undergraduate and graduate students do the dirty work of recovering artifacts that will likely be translated into a professor’s academic article.

Once the visit at the Hidatsa site concluded, I headed west across North Dakota to the eastern edge of Montana and another new time zone. Most of my time riding through North Dakota saw relatively flat lands covered with corn, soy beans, and more corn. But not all of North Dakota is flat as I discovered on a very windy ride through the northern edge of the North Dakota Bad Lands. Strikingly beautiful and absolutely unsuited for farming, even the edge of the Bad Lands was worth stopping to take a picture.

A west wind was blowing at 25-30 mph with gusts near 40 mph when I went through here, and keeping the bike on the road kept me fully occupied. It was the third windiest day I’ve ever ridden through.

One final note on this long blog. After a shaky start to this trip, my bike seems to be holding up fine, though it’s nearly as dirty as it was on trips up and down the Alaska Highway. Lewis collected hundreds of plant and animal specimens. I have too but I don’t think mine are identifiable. Today the odometer rolled over 90,000 miles. Not bad for an old bike with an old man piloting it.

Tomorrow, something different, I think.

MHT Day 11: Notes on Natives

On the evening of September 24, 1804, the expedition, having gone 13 miles up the Missouri River that day, encamped a couple hundred yards from where I encamped last night at the Holiday Inn Express in Ft. Pierre, SD. The next day, during a meeting between the expedition and the Teton Sioux, trouble arose when a lesser chief believed he had been slighted in the exchange of gifts and several Teton attempted to seize one of the small pirogues. The fracas, alarming at the time, didn’t amount to much and ultimately the Captains and several other crewmen were feted by the Sioux in their camp and continued their voyage upriver the next day with scores of Indians following along on the bank. Although no further serious confrontation erupted, the crew and captains were pleased to leave the troublesome Sioux behind.

Most of the Indians the expedition met were friendly and helpful, but the Sioux were a different matter. The Sioux harassed, raided and warred on neighboring tribes, stealing provisions and taking women and children captive. On both the outward and return legs of their journey, some of the Sioux presented problems for the expedition, a development Lewis and Clark had expected before setting out from St. Louis.

Oahe Dam and Lake north of Pierre, SD

The river where the Teton Sioux encounter occurred is very much changed from when the Corps of Discovery saw it. The building of the Oahe earthen dam just north of Pierre (pronounced “peer”), South Dakota’s capital city changed everything. Going east to west, the Oahe is the third in a series of six dams which have forever altered the Missouri River. Today, I rode more than 200 miles parallel not to a river, but to a very long lake full of weekend pleasure boaters and anglers. And the three biggest lakes are still ahead of me.

The proposal for six dams was made as part of a comprehensive flood control and hydroelectric project in 1944 and the Oahe Dam was completed in 1962, flooding hundreds of thousands of acres and displacing Sioux living on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, as well as other Indians on other reservations. Not only were more than 50,000 acres taken from them, the land that was flooded was among the best agricultural land on the reservation. They were promised compensation but it never materialized and in 2019 the Sioux are still fighting to be properly reimbursed for the theft of their land.

The Sioux and other tribes Lewis and Clark met in 1804 and 1806 were relative newcomers to this land, having migrated to it from the east and the north beginning about 350 years ago. The land had been inhabited by nomadic Indian peoples for thousands of years, perhaps as many as 12,000 years ago, and evidence of them has been found in hundreds of archeological digs. Years before Lewis and Clark arrived, the natives had already suffered calamitous setbacks to their lives and culture, mostly through the introduction of smallpox and other devastating diseases brought by French and Spanish explorers and traders.

A good example of this effect is seen in the Mandans, who occupied the area near where I finished today’s ride at Bismark, ND. At a stop at Abraham Lincoln State Park, about 25 miles from the North Dakota state capital, I toured a site mentioned by Clark who wrote about it on October 20, 1804.

I saw an old remains of a villige on the Side of a hill which the Chief with us Too né tels me that nation (Mandans) lived in a number villages on each Side of the river and the Troubleson Seauex caused them to move about 40 miles higher up where they remained a fiew years & moved to the place they now live

The site, covering 6 to 8 acres with archaeological evidence of at least 68 family dwellings and a large council lodge, is known as On-A-Slant village because of its position on the side of a hill overlooking the Missouri River. When Clark and others of the expedition saw the remains of the village, it had already been abandoned and burned by the Mandans. Why? Because after a devastating smallpox epidemic swept through it in the 1790s there were no longer enough men left to defend those who survived the disease from raids by their Sioux neighbors to the south. So the remaining members of the tribe packed up and moved north where they were joined by Arikara survivors of their own smallpox epidemic.

As a side note, about 1/2 mile from On-A-Slant village, the U.S. Army built a fort and then a cavalry post in the years after the Civil War. At one time the post was commanded by Lt. Col. George A. Custer, but he went on a military expedition in 1876 and never returned. Fort Abraham Lincoln State Park contains both the On-A-Slant Village site and the Fort and both were partially reconstructed by the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) during the 1930s.

A lone soldier stands guard on the porch of Lt. Col. George Custer’s reconstructed house.

I had planned to go to another site today in Bismarck at the North Dakota State Museum but ran out of time. A road sign on SD 1804 north of Mobridge indicated the road was closed to trucks 23 miles ahead. But 23 miles later when I got to that point the road was closed to all traffic, so I had to backtrack, losing an hour in the process. But at least today wasn’t as hot as yesterday and the scenery of rolling hills and high wispy clouds was enjoyable.

MHT Day 10: Exploring the Great Plains

For the first 40 miles today, beginning at 7 a.m., I rode north on Interstate 29, which parallels the Missouri River and rarely was more than half a mile from it. I chose the Interstate to start the day because I knew I had 350 miles to cover and several stops to make along the way. And it was going to be HOT.

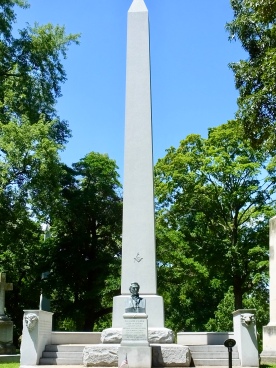

Beneath the obelisk lies Sergeant Charles Floyd, the only fatality among the expedition.

Despite all the hazards, dangers, and accidents that befell the members of the Corps from 1804 to 1806, only one member of the group died during the expedition. Sergeant Charles Floyd, a 22-year old Kentuckian, had been picked up when Clark joined Lewis in Clarksville in 1803. He quickly caught the captains’ attention and was promoted to sergeant while the expedition wintered at Camp River Dubois. On August 20, 1804, after several days of incapacitating stomach pain probably related to a burst appendix, he died just south of present day Souix City, Iowa

The view from Sergeant Floyd’s burial site south of Souix City.

He was buried with honors by the Corps and now lies beneath a 100 foot tall obelisk on a high bluff overlooking the Missouri River. That site is approximately 40 yards east of the first burial because his original grave had been disturbed when the bluff began to fall away into the Missouri River This morning, I paid my respects to the voyage’s only fatality.

At Souix City, the Missouri turns west again for 150 miles, with Nebraska to the south and South Dakota to the North. More importantly, the area consists of extensive plains that, for the most part, stretch from the eastern borders of Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota all the way to the Rocky Mountains. There were, of course, hills that bordered the Missouri River, but beyond the river bottoms and the defining hills lies a vast, largely treeless prairie inhabited by thousands of animals that astonished the frontiersmen of the expedition, whose life east of the Mississippi had not prepared them for the country they were exploring. One of the best early descriptions of the western plains came from Captain Lewis on September 17, 1804, following a walk through the South Dakota country through which I rode today (don’t blame me for the spelling; that’s all on Lewis):

this plain extends back about a mile to the foot of the hills one mile distant and to which it is gradually ascending . . . . the shortness and virdue [verdure] of gass gave the plain the appearance throughout it’s whole extent of beatifull bowlinggreen in fine order. … found the country in every direction for about three miles intersected with deep revenes and steep irregular hills of 100 to 200 feet high; at the tops of these hills the country breakes of as usual into a fine leavel plain extending as far as the eye can reach. from this plane I had an extensive view of the river below, … to the West a high range of hills, strech across the country from N. to S and appeared distant about 20 Miles; they are not very extensive as I could plainly observe their rise and termination no rock appeared on them and the sides were covered with virdue similar to that of the plains this senery already rich pleasing and beatiful, was still farther hightened by immence herds of Buffaloe deer Elk and Antelopes which we saw in every direction feeding on the hills and plains. I do not think I exagerate when I estimate the number of Buffaloe which could be compreed at one view to amount to 3000.

From a bluff overlooking the Missouri River near where Lewis wrote his description of the endless plains.

My second historical site stop for the day was Spirit Mound, about 4 miles north of Vermillion, SD. From the Lakota people they met along the river, members of the expedition had heard about Spirit Mound, a small hill believed to be occupied by mysterious and possibly dangerous little people. Regarding the hill, Clark recorded on August 24, 1804, that “by all the different Nations in this quater [it] is Supposed to be a place of Deavels or that they are in human form with remarkable large heads and about 18 inches high” The following day, Lewis, Clark and a small party walked from the encampment about four miles each way in the blazing heat to see the hill and, perhaps, the devils. They didn’t see them, nor did I. What they did see was vast herds of elk and bison, countless prairie dogs, coyotes dens, and the first bat they had seen on the trip. I didn’t see any animals except butterflies and dragon flies, but I did see on my two mile hike to the top of Spirit Mound and back a designated “National Historic Prairie” that botanists and biologists are restoring to the condition seen by Lewis and Clark, and that includes scores of native plants and flowers.

My final stop on today’s long, hot (95 degree) ride had nothing to do with Lewis and Clark, but was personally and historically significant. One of my Habitat for Humanity construction colleagues in North Carolina was formerly the President of Dakota Wesleyan University, a fine school, and the home of the George McGovern Library and Museum, which he played a major role in bringing to fruition. Dr. Jack Ewing had suggested if I was in the area I should stop by. It was only a 50 mile detour, so I headed for Mitchell, SD,

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, in the middle of the Viet Nam War and the anti-war protests, at the end of my turbulent undergraduate days I became involved in politics, protests and elections, especially that of Senator George McGovern, who in 1972 attempted to unseat Richard Nixon and bring honor, honesty, decency, integrity–all things that Nixon did not possess–back to the White House. McGovern a WWII recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross and holder of a Ph.D in History from Northwestern University, was soundly defeated by the crook in the White House in the landslide election of 1972. The following year, Nixon resigned in disgrace to avoid impeachment and certain removal from office; McGovern was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in August 2000 and the medal is in the museum. The first-rate museum dedicated to his amazing life and multi-faceted, humanitarian-based career brought back deep seated memories of my formative college days. Thanks for the suggestion, Jack.

Eleanor McGovern, George, and me, in front of the McGovern Library on the Campus of Dakota Wesleyan University.

Tomorrow I’m back on the trail with Lewis, Clark and the gang as I continue moving north along the Missouri River to Bismark, ND.

MHT Day 9: Lewis and Clark Turn North

On July 19, 1804, 20 days after leaving the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers where the Missouri makes a dramatic northward turn, the Corps of Discovery reached the point where I started my day, Nebraska City. For the first three months of the voyage, they had travelled through a wooded and rolling landscape along the Missouri River. Now they had reached the eastern edge of the great plains where enormous herds of buffalo, huge prairie dog towns, and packs of coyotes would fill them awe and wonder. Clark recorded in his journal that night that as he was tracking elk near the river he walked up a hill along the river and

after assending and passing thro a narrow Strip of wood Land, Came Suddenly into an open and bound less Prarie, I Say bound less because I could not See the extent of the plain in any Derection, the timber appeared to be confined to the River Creeks & Small branches, this Prarie was Covered with grass about 18 Inches or 2 feat high and contained little of any thing else, except as before mentioned on the River Creeks &c, This prospect was So Sudden & entertaining that I forgot the object of my prosute and turned my attention to the Variety which presented themselves to my view.

I chose Nebraska City because I wanted to begin the day with a visit to the Missouri River Basin Lewis and Clark Visitor Center, opened in 2004 as part of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial. The Center was also a convenient location for my brother Kent, who lives in Lincoln, to join me for the day as I followed the Lewis and Clark Trail north and broadened my knowledge about the expedition. As Kent and I examined a full-size replica of the keelboat outside the three-story, 12,000 square-foot Center perched on a bluff above the Missouri River, a gentleman approached and began to comment on certain elements of the boat. We soon learned that “Doug” was the Executive Director of the Center and we couldn’t have asked for a more helpful introduction to the site, which was organized, built and run by a non-profit organization with a strong partnership with the National Park Service.

As I go through museums and interpretive centers, I’m amazed at how much more I know after I leave them, especially if I interact with knowledgable staff like Doug and if the facilities have well-designed displays and exhibits. I knew, for example, that Lewis and Clark took frequent “celestial” observations, but I had not seen examples of the scientific equipment they carried nor did I know how it was used. Today I saw a display with a sextant, a spirit level and an artificial horizon instrument used in the early 18th century to determine fairly precise location and by which chronometers could be accurately set. Those instruments helped Clark measure their trip to an accuracy of 99 percent–he was off by 40 miles after making a 4,000 mile trek through the wilderness. After seeing that exhibit and the written explanation that accompanies it, I walked away with a much better understanding of the numerous journal entries they made when recording measurements.

These are examples of some of the scientific instruments Lewis and Clark used as they explored and charted new territory.

I also knew that among the expedition crew was a blacksmith, but I never fully understood how he went about his business until today when I saw a replica of the kind of portable forge complete with bellows carried as part of the expedition’s tons of supplies aboard the boat. Kent and I toured the entire building, but I know we missed many opportunities to learn more as I tried to keep to a schedule that would allow a visit to another important site up river.

When we finished our building tour, we walked down one of several trails maintained by the Center that took us to a Missouri River overlook. There we saw the river, still at flood stage, and the flooded farm fields on the Iowa side. Throughout the day, we saw other evidence of the devastating 2019 floods.

Kent and I strike our best Lewis and Clark poses as the Missouri River rushes by behind us.

Rather than return immediately to Lincoln, Kent decided to make a day of it and follow me to the next stop in Onawa, Iowa, at Lewis and Clark State Park. At least five of the six bridges over the Missouri River between Omaha, Nebraska, and St. Joseph, Missouri, are still closed because of the spring floods. I wanted to stay off the Interstate for a while anyway, so it didn’t bother me. But for the people who live in that part of the country, the consequences of a changing climate (e.g. 500 year floods every other year) must be taking a heavy toll.

I went through a few rain showers after we left Nebraska City, crossed the river at Omaha and headed north on I-29, but Kent said he stayed warm and dry in his car. I, on the other hand, was slightly damp, but dried out quickly after we arrived at Lewis and Clark State Park, the next stop on the Magical History Tour.

The small park boasts the only display in one place of replicas of all six watercraft used by expedition members during 1804-1806: The Keelboat (or Barge), two pirogues, a dugout canoe, Lewis’s iron-frame boat, and an Indian-style bull boat. One of the park staff, who went by his mountain-man re-enactor name “Lizard,” answered several questions I had (and several I didn’t have) about the various boats as we toured the site.

Although the park is not located on the Missouri River now, it was on August 9, 1804, when the expedition camped on the north side of the river across from what is now the park. The Missouri later changed course (as it frequently does), leaving behind an “oxbow lake” that is the state park’s focal point. The park has two full-sized replicas of the keelboat, one of which is tied up at a dock and carries tourists for rides on the lake Saturdays when the park is open. The boat inside the building is believed to be the more historically accurate of the two, but only one rough sketch and a couple of brief descriptions exist of the keelboat, and no one can know exactly what it looked like or how it was built. Nevertheless, boat builder Butch Bouvier conducted extensive research on early 18th century riverboats before and during the construction of the replicas and did his best to accurately represent the craft.

Kent had spent a full day following his big brother, and it was good to spend time with him. He, like I, learned a lot about the expedition and the watercraft they used; he decided Lewis and Clark State Park might be a nice place for a family vacation. I wandered around a while longer, had another conversation with Lizard about the expedition’s use of bull boats (he was strangely unfamiliar with that part of the journey), then left the park and ended my explorations for the day.

The courageous explorer surveys the horizon for dangers lurking in the water.

Tomorrow I’ll continue north, with plans to stop at sites where historians know members of the expedition visited. Sunny skies should return, but so will the heat so I hope to get an early start.

MHT Day 8: A Personal History Detour

Tomorrow I’ll get back on the trail of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, including a couple of interesting and highly anticipated sites. But today was a personal day that meant a lot to me but probably won’t mean much to anyone else.

Yesterday’s ride ended in Topeka at my childhood friend Jaylene’s with a late-night filibuster featuring our families, classmates from the class of ’65, and various discussions as we caught up on our personal news.

Today was more of the same. Several days ago, during the three-day delay waiting for my bike to be repaired, I saw a FaceBook post from the Topeka West High School group reminding those who followed it that their monthly lunch would take place today. I counted the days, estimated the stops along the way and discovered I would be in Kansas City, only 50 miles from Topeka on the Tuesday before. With no set schedule to keep, I decided to take a day off and have lunch with high school classmates I hadn’t seen in more than 50 years. So I stretched yesterday’s ride an additional 50 miles, enjoyed a fine Italian dinner and spent a very talkative evening with Jaylene Today I pursued some local personal history.

After helping Jaylene put together a new base for a new TV this morning, I mounted my bike to tour some of my old haunts. I rode slowly past my old grade-school (A. J. Stout Elementary) where I first met the cohorts who would join me in the difficult 10-year transition to adulthood , then headed for the house in which I grew up to take a quick look there. When I pulled up in front of the house, I hailed an elderly gentleman sitting on the porch, introduced myself and explained to him that I had lived in that house during my school years until I left Topeka for the Navy in 1965. We chatted a while, then to my surprise and delight, Mr. Gurwell invited me inside. Several changes had been made over the years (doors disappeared under drywall, faux hardwood floors replaced worn carpets, wallpaper covered dining room walls which my mother had carefully stripped of wallpaper), but it was largely as I remembered, including the original 100-year old kitchen cabinets and the original wood french-door frame between the dining room and the living room. He didn’t go upstairs much any more, he said leaning on his walker, but said I was free to take a look at my old bedroom if I wanted to. There had been significant changes there, too, but enough remained to bring back youthful memories that had fallen into the deep abyss of my mind. I walked once more down the stairs I had been up and down thousands of times before, we talked more about a few other changes in the house, and I took my leave after thanking him again for giving me a chance to refresh fading childhood memories.

Mr. Gurwell stands on the front porch of my former home. Note that when my family lived there from 1953 to 1965 the address was 2216; it has since been changed by the city to 2142 to more accurately reflect its location on the 2100, not 2200, block of Jewell Avenue. It was also white the entire time we lived there.

Someday the house may become a shrine in my honor (or not) but it will always produce important family memories for me.

Next stop on today’s personal history tour was the FaceBook-advertised lunch with former classmates. Eight members of the class of ’65 showed up at Annie’s at noon and for nearly two hours we related decades of our lives to one another, talked about other classmates living and dead, discussed teachers and administrators we remembered, and shared high school experiences that were both meaningful and trivial. I had only known one of them well but today spoke longer with all the rest of them in two hours than I spoken to them during three years of high school five decades ago. We all probably would have had more fun in school if we had been as open and friendly then as we were today. It’s amazing how much we matured during 50 years.

Older but MUCH wiser, members of the class of ’65.

After loading my bags again, taking the obligatory picture with Jaylene to remind us of how six decades had changed two grade-school friends, I pointed the bike north and rode two hours to Nebraska. Tomorrow I’ll be with brother Kent for a few hours and visit several top-notch Lewis and Clark historical exhibits as I continue to follow the Missouri river upstream to its source, as did the Corps of Discovery more than two centuries ago.

Note the quilt behind Jaylene. Marilyn made it for her birthday this year.

MHT Day 7: Across Missouri to Kansas

On June 26, 1804, 43 days after leaving Camp River Dubois, the Corps of Discovery reached the Kaw (Kansas) River where the Missouri turned north. That month and a half had been filled with hardships, dangers and significant tests to the mettle of all those involved in the expedition. That day, Clark recorded in his journal that the boats had “passed a bad Sand bar, where our tow rope broke twice, & with great exertions we rowed round it and Came to & Camped in the Point above the Kansas River.” But that day had not been unusual; everyday presented a trial of one sort or another. Still, the captains decided to spend three days at that point, repairing their boats as needed, taking a series of observations necessary to create accurate maps, and probably just resting a little before proceeding on.

Half size model of the keelboat in Boonsboro. It seems as though every museum wants to get a piece of the keelboat action.

Today, I also reached that point at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers after riding nearly 200 miles on backroads from Columbia in the middle of the state. I had four destinations in mind today when I started out and I managed to spend time learning something new at each location. On June 8, 1804, the expedition had reached the area near Boonsboro and I took a look at how the folks there memorialized the visit. In a small but nicely done museum, the folks at Boonsboro displayed a half-size model of the keelboat that was useful in showing how the interior of the stern cabin had been arranged with sleeping quarters for the two captains.

The historic tavern at Arrow Rock would have been a good place for a late breakfast, but the cleanup crews still have some work ahead of them to fix fire damage.

About 15 miles down the river the next day, the flotilla passed by Arrow Rock so I made that my next stop, anxious to see the rock. Except that there wasn’t really an Arrow Rock. At the Arrow Rock Interpretive Center I learned that the name was derived not from a singular, arrow-shaped rock but rather from the fact that the Osage Indians who lived in the area used rocks from a bluff near the river to make arrows. I also discovered that the river can’t be seen from the bluffs because of the heavy tree growth. So I strolled around the town of the same name, looking for the Huston Tavern, an eating establishment which had been billed as the oldest continuously operating restaurant west of the Mississippi. Once again my expectations were dashed because the tavern was temporarily closed thanks to a fire in May which had caused considerable damage to the kitchen. They had a tent set up where they served food, but somehow it wasn’t the same as an historic tavern.

Fort Osage is an impressive site built under the auspices of a county government.

Westward I proceeded to Fort Osage, located high above the Missouri River. The fort was not there, of course, when Lewis, Clark, et. al., rowed by, but Clark, at least, must have thought the site special because after he returned from the expedition and was promoted to Superintendent of Indian Affairs in 1808 he ordered that a fort be built there not just for defensive purposes but to serve as a trading post to bring the Indians into a commercial relationship with the United States.

Site director Fred Goss walked me through the fort’s history.

The site, run by the Jackson County Parks Department is impressive, containing a reconstruction of the fort on the ground where the original had stood and a modern museum and educational center. I spoke with Fred Goss, the site administrator, for nearly 30 minute as we walked around the site and he pointed out significant features and answered my questions about Clark’s role in removing Indians from lands they had occupied for thousands of years. In the year the fort was built, the Osage signed a treaty that began the rapid diminution of tribal lands. Within 40 years they had signed away most of what they occupied for countless generations.

Cutouts of Lewis and Clark point the way north up the Missouri with the skyline of Kansas City, Missouri, in the background.

Finally, I was on to Kaw Point Park in Kansas City, Kansas, which is where they landed on June 26. Built in honor of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in 2004, this site is the location of frequent re-enactments of the three-day stay in 1804. Much of the site was covered with dried mud from the recent floods, but the perspective of the two rivers coming together was worth the stop.

My final stop for the day was in my old hometown of Topeka where I joined a dear friend from grade school, junior high and high school days for dinner and a talk that lasted well past mid-night. I had gone from exploring history of two centuries ago to reminiscing about a much more recent past. Now it’s very late ( 2 a.m.) and the quality of this blog probably shows it.

One more note: I rarely take Interstate or major highways when I’m traveling since everything flashes by without having time to properly appreciate it. On the Interstate I never would have had the opportunity to stop at a fresh fruit stand and eat the biggest, juiciest peach I’ve seen in a long time. That peach was my lunch today–what a treat.

MHT Day 6: A Changing River

Today I traveled in about seven pleasant hours what the Corps of Discovery in 1804 managed in a little more than two labor-intensive, back-breaking weeks. From May 20 when they left St. Charles to June 4 when they passed the spot where Jefferson City, Missouri’s capital, now stands they covered about 125 miles up the river, or fewer than 10 miles per day. I actually rode nearly 200 miles, but there were some expected and unexpected detours involved.

The expedition group numbered about 48 men as it made its way up the Big Muddy, including 28 members of the permanent party who would go on to the Pacific, about 8 members who were scheduled to return to St. Louis before winter set in, and another dozen laborers, mostly French boatmen hired in St. Louis who knew the river and how to handle large boats in its dangerous currents.

For most of the day, I followed roads that advertised the Lewis and Clark Trail with this sign. I’ll follow similar roads for the next 5,000 miles or so. (I’ve only logged 1,200 so far.) The National Park Service uses this sign to let motorists know they are about as near to the actual route of the expedition as they can be short of paddling or walking it. It will be a friendly reminder that I’m headed in the right direction as the miles roll by during the next three weeks or so.

For most of the day, I followed roads that advertised the Lewis and Clark Trail with this sign. I’ll follow similar roads for the next 5,000 miles or so. (I’ve only logged 1,200 so far.) The National Park Service uses this sign to let motorists know they are about as near to the actual route of the expedition as they can be short of paddling or walking it. It will be a friendly reminder that I’m headed in the right direction as the miles roll by during the next three weeks or so.

One reason the Corps of Discovery took so much longer is that the Missouri River, as difficult as it is to navigate today in non-motorized craft, was a beast in 1804. It was much wider (more than 1/2 mile wide then, less than 1/4 of a mile now) and the surface area of the river water between here and St. Louis was three times greater. Oh, and the Army Corps of Engineers hadn’t begun to straighten the river and remove all the debris that spring floods uproot and deposit in terrible tangled masses to the great hazard of boatmen who couldn’t always see the snags.

Strong storms several hours before departure today made the roads a little slick, but they dried out before noon and at least I didn’t have to ride in the rain.

I, on the other hand, after a damp beginning, travelled some very nice asphalt roads in balmy temperatures, roller coasteering up and down the hills of rich farm country that stretched for miles on either side of the road. There was one section of Highway 100 not far from the river that was still closed either by debris on the road, or, more likely, water. I had expected the detour and anticipated which roads I would need to take on my alternate route. What I had NOT anticipated was that one of the roads called for in the detour was gravel, so, not knowing the condition or the length of the rocky road, I added a detour to my detour that padded today’s ride by about 25 or 30 miles. But it was beautiful countryside, and I sat back and enjoyed the scenery that whizzed by.

Stop One: The John Colter Memorial in New Haven on the banks of the Missouri.

I had planned three stops today at sites related to the expedition. First was a modest memorial to one of the crew’s better-known members: John Colter. Historians believe Colter had been picked up by Lewis in Pittsburg or shortly after leaving there as a “trial” member. Other than a couple of disciplinary matters which were resolved without much ado, Colter quickly became one of the expedition’s best hunters. He made it all the way to the Pacific and most of the way home, but when they got to within about 1,000 miles of St. Louis on the return, Colter asked to be released from service early; he wanted to return to the country they had just explored and seek his fortune trapping beaver. The seasoned mountain man made an infamous escape from the Blackfeet Indians after returning west and was probably the first European to see the extraordinary geysers, mud pots and canyons in what is now Yellowstone Park in Wyoming. Within a decade, he gave up trapping and the dangers of life in the west, bought a farm in Missouri near New Haven, and died and was buried there in 1812. In 2004, during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial, local folks erected the memorial in his honor.

The view of the Missouri River from the top of Clark’s Hill.

The second stop was Clark’s Hill or Norton State Park about 20 miles east of Jefferson City. This was a rocky outcrop on a bluff above the confluence of the Osage and Missouri rivers where the party stayed for two days to take surveying and celestial measurements and was described by Clark in his journal entry for June 2, 1804: “. . . from this pt. which Comds both rivers I had a delightfull prospect of the Missouries up & down, also the Osage R. up.” I knew it was accessible and wanted to see what Clark had seen. So I rode half a mile down a potholed dirt road, hiked a mile up the hill and saw . . . Trees! Nothing but trees! I knew the Osage River had changed course about 100 years ago and now emptied about five miles further downstream. But I also knew–or thought I did–that the Missouri River was still there. Near the top of the trail I met, Linda, a volunteer working for the Missouri Natural Resources Department trying to remove invasive species along the trail, who explained to me that the Army Corps of Engineers had in the last 30 years or so deepened the river channel on the northern side, which in turn made the river narrower and the bottoms wider, which in turn provided a prime spot for cottonwood trees to thrive, which in turn blocked MY view of Clark’s view. Oh well, it was pleasant hike, and I had nice conversation with Linda while I caught my breath for the downhill return.

Finally, I wanted to stop at the State Capitol and Museum in Jefferson City, because I had read that it contained a few items and memorials related to Lewis and Clark. Once again, I was a little disappointed in what I discovered. First, the Capitol is undergoing major renovations to prepare for the state’s upcoming bicentennial and it’s wrapped up like some weird Christmas present while workers clean the exterior surfaces. And there’s green chain-link construction fencing all around which prevents weary motorcycle riders from getting too close.

One item in particular I hoped to see was a statue of one of my favorite presidents, but they had the city’s namesake in a cage. I’m not sure if they’re making a political statement given the current administration’s predilection for putting people in cages or whether it’s just part of the construction process.

One item in particular I hoped to see was a statue of one of my favorite presidents, but they had the city’s namesake in a cage. I’m not sure if they’re making a political statement given the current administration’s predilection for putting people in cages or whether it’s just part of the construction process.

In the museum inside the Capitol, I learned that the limited exhibit space was given over to a centennial look at Missouri’s role in WWI and to the upcoming bicentennial. They did have two large statues of Lewis and Clark in the rotunda but they were set back in dark alcoves and didn’t do much for me. On the outside, on the Capitol grounds, I finally found a fairly decent memorial erected during the Lewis and Clark bicentennial in 2004-2006. Although I think the artist took liberties with the appearances of the figures in her tableau, it was nice to see Clark’s slave York (they referred to him as Clark’s “man-servant”) and French-Indian George Drouillard included in the group.

York, Lewis, Seaman, Clark the mapmaker, and Drouillard, York and Drouillard are just guesses, of course, since there are no portraits of them available.

I had several good looks at the Big Muddy as I crossed it and stopped next to it several times today. Today’s river is mighty, but it’s a far cry from the wild river that the Corps of Discovery ascended in 1804.

MHT Day 5: The Corps’ Journey Begins

From the middle of December 1803 until the middle of May 1804, the captains made final arrangements for the historic voyage that would answer President Jefferson’s questions about a water route to the Pacific, the nature of the new land and its peoples acquired through the Louisiana Purchase, and the commercial and trade potential for the western portion of the United States. For Clark, that meant instilling military order and discipline to a permanent party that grew to 28 men. At the same time, he also had to determine the skills each man possessed and how they could be harnessed for the good of the party. Some of the recruits were well-behaved and reliable, while others needed to be molded by Clark’s firm hand before they could find a place in the Corps.

For Lewis, that five-month period meant spending much of his time several miles down stream in St. Louis or one of the nearby communities gathering additional supplies and working through the political tangles caused by Spanish occupation of French territory that was soon to be American soil. Although the Louisiana Purchase was ratified by the U.S. Senate in October 1803, the official transfer in St. Louis didn’t occur until March 1804 and involved the Spanish representative turning the territory over to the French who held it for one day before turning it over to the Americans. Lewis, still the private secretary to the President, was on hand to witness and sign the transfer document in March 1804. Firm possession of the Louisiana Purchase made an American military expedition up the Missouri River much easier, though little about the next two and a half years would be easy.

By May 1, the men of the Corps had gelled into a regular army unit and were ready to begin their voyage. Clark had them pack and repack the 55-foot keelboat which had been outfitted with additional storage lockers and prepare and pack the two pirogues (39 feet and 41 feet). They were, after all, taking with them about 12 tons of supplies.

On Monday, May 14, 1804, Clark wrote in his journal:

Set out from Camp River a Dubois at 4 oClock P. M. and proceded up the Missouris under Sail to the first Island in the Missouri and Camped on the upper point opposit a Creek on the South Side below a ledge of limestone rock Called Colewater, made 4½ miles, the Party Consisted of 2, Self one frenchman and 22 Men in the Boat of 20 ores, 1 Serjt. & 7 french in a large Perogue, a Corp and 6 Soldiers in a large Perogue. a Cloudy rainey day. wind from the N E. men in high Spirits

Finally, after years of planning, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was underway. Except that Lewis wasn’t with them. He was still in St. Louis and would join the group about 20 miles west at the village of St. Charles on May 20. OK, then the Lewis and Clark Expedition could get underway.

The Gateway Arch in St. Louis is hard to miss.

My day was spent at two locations in St. Louis and one in St. Charles learning about the St. Louis Lewis and Clark saw, the preparations they made, the craft they sailed (or rowed, or poled, or towed as conditions demanded), and the expedition leaders’ traits and personalities. First, I went to the iconic Gateway Arch, not to ride to the top to see the view from Missouri’s tallest structure, but to explore the interpretive museum at its base. Given a huge budget, experts can put together truly first-rate museum exhibits and the Gateway Arch museum is no exception. I discovered the history of St. Louis: Native American for thousands of years, then the Spanish to a small degree followed by the French who arrived both from Canada and by way of New Orleans, and finally the Americans. St. Louis itself was officially founded by the French in 1764 though its position at the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi rivers had made it a Native American trading and commercial center for a thousand years. I pressed several park rangers into service to fill in some of the blanks not satisfied by the exhibits and left with a clearer understanding of frontier St. Louis and the international politics Lewis contended with.

Interactive exhibits and well-displayed artifacts abound in the Gateway Arch Museum.

William Clark showing a fine queue.

My next stop was Bellefontaine Cemetery (aka Bell Fountain in the anglicized patois), one of the city’s largest cemeteries with about 87,000 interments on 350 acres. Who was there that piqued my interest? General William Clark, who, after returning from his voyage with Lewis, was promoted to Brigadier General, named governor of Missouri Territory and appointed Superintendent of Indian Affairs for all land west of the Mississippi. Clark died in 1838 at age 68 after a long life as a soldier and a statesman. I read inscriptions on various memorial stones at the site, then sat for a while and reflected on what he and Lewis and their men had done. I concluded, like many others, that the ledger of his life had a mixed result. On the plus side, he was brave, honorable, fair, and sought justice for those in his charge.

Clark’s obelisk at Bellefontaine Cemetery. He is buried there with his second wife and three sons.

But at the same time the tragic results that his expedition helped accelerate for native cultures and thousands of native people cannot be understated. He knew what was happening as well as anyone, but was unable to alter the course of history he had helped set in motion. In 1825, he wrote to his old friend Thomas Jefferson, “It is to be lamented that the deplorable situation of the Indians do not receive more of the human feelings of the nation.”

Finally, I headed to St. Charles where the Corps stopped on its second day on the river to wait for its co-commander. In 2004, a group of re-enactors based in St. Charles but drawing its membership from far and wide, built and set sail in three accurately built replicas of the boats used by the Corps, going up the Missouri River to Mandan, North Dakota, in the keelboat and continuing on to Great Falls, Montana, in the two pirogues. Following their maiden voyage the boats were stored in a new boathouse and museum facility on the north bank of the Missouri River in St. Charles.

Several replicas of the keelboat will be available on my route west, but this was the first opportunity I had to see full-scale models of all three. Although the boats are not well-displayed for most visitors to see since the boathouse is mostly for storage of the boats, I met one of the re-enactors today who was hard at work cleaning up from this year’s flood, which deposited six feet of water and a foot of mud in the boathouse. He opened the heavy grated door and invited me to look around and see the boats in a way most visitors do not. We talked about the boats, their construction and their use, but we also talked about this year’s flood and how it compared to previous years’ floods. He reminded me that the Missouri River, when the Corps plied its waters, was much wider than now but much also much shallower. Constant dredging along the river’s course has deepened the channel and sped up the flow.

Some reminders of this year’s flooding line the bank next to the boathouse in St. Charles.

One final note: Today I visited two museums. One is well-funded by public monies and clearly the work of professional historians, exhibit designers and curators. The other is a volunteer effort maintained by donations and perhaps some small grants. The two were strikingly different, though each is important in its way and each helps preserve, interpret and display America’s past. I’m glad both exist and glad I was able to visit and learn at each of them.

Meriwether, Bill, Seaman and me in St. Charles. They were truly giants.